…if it’s unrealistic to suppose that smart machines can be stopped, it’s probably just as unrealistic to imagine that smart policies will follow.

(Elizabeth Kolbert, New Yorker, December 19 and 26, 2016)

Yet another example of flawed thinking

Every installment should begin with recent examples of flawed thinking about the future of machines in mathematics. Even without trying I see a new one every week or so. Here’s one dated March 7, 20221, published in Quanta:

It will be a long time, if ever, before mathematicians cede their field to machines.

As usual, the misunderstanding here concerns the human beings rather than the machines. Mathematics is not a business2 that aims to produce a provisionally marketable commodity like buggy whips. Earlier on this site I pointed out that, before preparing a course with the title What is Mathematics?,

…one will need to decide what kind of thing mathematics is. Familiar options include “art,” “science,” “technique,” “discipline,” “profession,” “vocation,” “tradition-based practice.” Will “a way of being human” be one of the course’s options?

I neglected to include “commodity” in the list, but it is the only “kind of thing” that mathematics could be if it made any sense at all for mathematicians to “cede their field to machines.” The “product” of mathematical practice, if one must call it that, is a form of human experience and human sociability. It is no more coherent to speak of ceding human experience or sociability to machines than to wonder whether we will soon be inviting robots instead of humans to our dinner parties. In other words, it only makes sense if one has reason to think of the machines as human.

The flawed sentence appeared in an article by Leila Sloman entitled “In New Math Proofs, Artificial Intelligence Plays to Win.” Sloman is identified as a “writing intern,” which means Quanta’s editors, rather than the author, are primarily to blame for propagating this misconception. Do the editors really believe that this narrative about human mathematicians makes sense, or do they just think it lends helpful suspense — “human-level,” existential suspense — to an otherwise technical report? If the latter, it’s probably incurable. But let’s try to keep agency where it belongs: it was the buggy’s driver, and not the buggy itself, who ceded the field to the automobile, and once the retreating humans “cede their field” to the machines the pathos will be drained from the narrative — no more talk of ceding anything as one generation of machines gives way to the next.

Applying for exemptions

More sophisticated authors also indulge in such hazy speculation about human obsolescence. On the first page of his potentially pathbreaking article “How can it be feasible to find proofs?” Tim Gowers writes

My own guess is that I won’t live to see computers take over completely – I am 58 – but that I will live to see exciting progress in that direction.

The only sense I can attach to a situation in which “computers take over completely”3 has the computers as readers as well as authors4 of mathematical proofs. Nothing prevents us from imagining new generations of player pianos that compose as well as perform — adapting each performance to meteorological or astrological or whatever conditions — for an audience entirely consisting of player pianos (of many different shapes and sizes). If being “taken over completely” left me desperate for work I could even write the copy on promotional materials, insisting that anyone who refuses to call that “exciting progress” is a Luddite.

Picture Skynet’s letter of dismissal to guitarist Bill Frisell, who at age 71

still feel[s] like I’m barely even scratching . . . just barely starting. That’s the nature of music: it just doesn’t end. There’s no way you’re ever gonna finish, and anyone who ever says they’ve got it all together is lying. Every day you wake up and see what you haven’t yet done with music. It’s infinite, what’s out in front of you. I’m just trying to stay healthy so that I can keep doing it.”5

It’s safe to assume the mathematicians among my readers are nodding in recognition and have associations with “every day,” “wake up,” and “stay healthy” that would challenge a machine. Computers will not have “take[n] over completely” until and unless they preserve the mathematical equivalent of each of Frisell’s “scratches.”

A magnanimous Skynet, sensitive to the possibility that every aspect of the experience to which Frisell refers is a precious resource that may some day even be marketable, might make the following offer: if at age 30 you’re on track to become a Bill Frisell, or a Bill Thurston, or a Bill McKibben, or a Bill Russell, you will get an exemption to participate in the musical or mathematical or whatever project. If not, it’s off to the Hunger Games with you.

And what about Bill de Blasio, while we’re on the subject of Bills? Have the journalists and colleagues who blithely anticipate the end of human music or mathematics drawn a clear line of demarcation between those activities and “everything else”6? For all the hand-wringing about mistakes in published proofs or gaps in arguments based on unpublished material, I hope my most technophile colleagues will agree that mathematicians (and musicians) are much much better at getting things right than any politician you can name. We might not be debating mechanization of mathematics at all had not Leibniz, that notorious optimist, proposed to resolve all political and other conflicts by means of his Universal Characteristic, a hypothetical system modeled on formal logic:

Who among politicians in recent memory could claim to be indispensable if such calculations were possible and if, as we learn in the first Terminator film, the “new… powerful” Skynet itself were

Luddism, automation, and the class struggle in (my) historical perspective

Let’s suppose for the sake of argument that a thoroughgoing determinist, convinced that my belief in my own free will is an illusion and that I am also merely a plaything of historical or biological forces, sought to explain my propensity to sympathize with what some would call Luddism. Suppose this determinist wanted to reverse engineer me, rather than someone valuable, like Poincaré. What predisposed me to be skeptical of promises of “the exciting benefits of a new machine age — of increasing productivity, advances in medicine, greater convenience, and very cool gadgets?7”

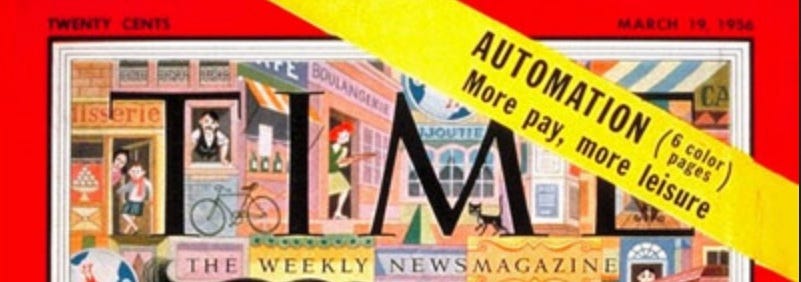

My childhood memories turn out to be accurate. Concern about “automation” was in the air when I was growing up. Even President Kennedy was worried:

John F. Kennedy, News Conference, February 14, 1962

A few years later, AFL-CIO president George Meany warned that automation was

rapidly becoming a curse to this society … in a mad race to produce more and more with less and less labor and without any feeling [as to] what it may mean to the whole economy.8

With hindsight it’s possible to perceive the material interests behind the push for replacing workers by machines. For example, historian Timothy Mitchell sees the turn to oil, in part, as a reaction to coal miners’ ultimately frustrated attempts to defend their autonomy, in part against mechanization:

The militancy that formed in these workplaces was typically an effort to defend this autonomy against the threats of mechanisation, or against the pressure to accept more dangerous work practices, longer working hours or lower rates of pay.”9

Marc Levinson, on the other hand, sees the longshore industry as “a rare exception”:

The days of long-established gangs working together, of casual conditions that let men work when they wanted to work and fish when they wanted to fish, would never be regained, as work once marked by independence and freedom from control became a high-paying but highly structured job.

Despite these discontents, the longshore unions’ tenacious resistance to automation appeared to establish the principle that long-term workers deserved to be treated humanely as businesses embraced innovations that would eliminate their jobs. That principle was ultimately accepted in very few parts of the American economy and was never codified in law. Years of bargaining by two very different union leaders made the longshore industry a rare exception, in which employers that profited from automation were forced to share the benefits with the individuals whose work was automated away.10

Although this looks like a happy ending, the passage is disturbing for its formulation of the “principle,” widely rejected and “never codified in law,” that a certain category of workers “deserved to be treated humanely.” Ultimately, this passage reminds us, the question — who treats, who is treated? — is resolved by “resistance,” “bargaining,” and “force”: not the impersonal force of the arrow of history or of technological determinism but of power relations between two groups of human beings. This — and not name-calling or hand-wringing about the failure of the fading generation to get with the program — is where any discussion of the historical role and contemporary revival of Luddism has to begin.

And it is no less imperative to keep power relations in mind when speculating about “mathematicians ced[ing] their field.”

Readers of the Financial Times need have no illusions about the power relations masked by the rhetoric of technological determinism:

Big Tech’s business model is about getting rid of human labour and turning human behaviour into a raw material. (Rana Foroohar, Financial Times, January 30, 2022)

Even the utilitarian John Stuart Mill “urged… in his influential case for free trade: in dropping trade barriers, workers and other losers from imports should somehow be compensated.”11 Gavin Mueller’s Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites are Right…12 argues that “to be a good Marxist is to also be a Luddite.”

technology developed by capitalism furthers its goals: it compels us to work more, limits our autonomy, and outmaneuvers and divides us when we organize to fight back.

Luddism is typically decried as a short-sighted reaction to technological developments that are not only inevitable but that will ultimately create more and better job opportunities for the sectors that are temporarily displaced — as was the case during previous technology surges. A World Economic Forum report, entitled The Future of Jobs, anticipated in 2020 a net increase in employment:

by 2025, 85 million jobs may be displaced by a shift in the division of labour between humans and machines, while 97 million new roles may emerge that are more adapted to the new division of labour between humans, machines and algorithms.

That this will improve conditions for workers is not borne out by the evidence. According to a February 2022 study by economists Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, rapid automation promotes wage inequality, which in turn promotes the kind of political polarization we have witnessed in recent decades:

We document that between 50% and 70% of changes in the US wage structure over the last four decades are accounted for by relative wage declines of worker groups specialized in routine tasks in industries experiencing rapid automation.13

This all happened before the anticipated automation of 50% of all jobs by 2055, or by 2025, according to successive World Economic Forum reports.

According to J. M. Manyika, Chairman Emeritus of the McKinsey Global Institute, “acknowledging that this time could be different…” — in other words, that this round of automation will not create jobs to replace those that are lost —

…usually elicits two responses: First, that new labor markets will emerge in which people will value things done by other humans for their own sake, even when machines may be capable of doing these things as well as or even better than humans. The other response is that AI will create so much wealth and material abundance, all without the need for human labor, and the scale of abundance will be sufficient to provide for everyone’s needs. And when that happens, humanity will face the challenge that Keynes once framed: “For the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem–how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.”

That future sounds great! But not for me, and not for you:

However, most researchers believe that we are not close to a future in which the majority of humanity will face Keynes’s challenge, and that until then, there are other AI- and automation-related effects that must be addressed in the labor markets now and in the near future, such as inequality and other wage effects, education, skilling, and how humans work alongside increasingly capable machines…

(J. M. Manyika, Getting AI Right… Dædalus, Spring 2022)

Can technology keep its promises ?

Another sign of the flawed thinking that plagues every discussion I’ve seen of the propspect of mathematicians “ced[ing] the field” to machines is that it is never mentioned that mathematical research is mainly carried out in universities. Will university professors also be replaced by machines? And the students as well? There’s no room in this week’s installment to begin to sort this out. So let’s forget the workers for the moment and meditate on the supposed benefits to mathematics that the Luddites who try to hold back mechanization are doomed to enjoy, like it or not.

Will Tavlin explains what happened when Hollywood chose not to “hold back [digital] technology.”

Hollywood … developed a storage strategy [that] worked because film … is what’s known as a “store and ignore” technology: if placed in a properly controlled environment, it can survive for a hundred years, perhaps many more.

In contrast, The Digital Dilemma, a 2007 report by the Science and Technology Council at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

warned that digitally stored assets would not last for anywhere near a hundred years. Many of these assets … have “longevities of thirty years or less, and are vulnerable to heat, humidity, static electricity and electromagnetic fields. The digital contents can be degraded by accumulating unnoticed statistically occurring ‘natural’ errors, by corruption induced by processing or communication errors, or by malicious viruses or human action.” Magnetic hard drives, meanwhile, “are designed to be ‘powered on and spinning,’ and cannot just be stored on a shelf for long periods of time.”

And there’s the issue, forever plaguing all digital technologies, of obsolescence: both file formats and the hardware through which they’re accessed are designed to be updated or replaced by their manufacturers, meaning “digital ‘permanence’” requires an “ongoing and systemic preservation process” that includes regularly scheduled data migrations, in which data is periodically transported from old digital storage onto new storage.

The Academy report concluded that, claims of increased efficiency notwithstanding,

long-term archiving of digital cinema was spectacularly more expensive than its analog equivalent.14

Tavlin, in turn, concludes that “studio executives had been quick to accept digital technologies with no forethought or regard for the ‘most fundamental needs of motion picture production and preservation.’” He might have added that the studio executives exhibited a good deal of forethought and regard for the profits at the heart of their business model.

One of the “fundamental needs” Tavlin mentions is maintaining access to independent producers who cannot afford the “spectacular” cost of long-term digital archiving. The independent producers of mathematics in academia are now dependent on arXiv, which, although it is (for now) “financially supported by the U.S.-based Simons Foundation and an international consortium of academic institutions” is “understaffed and underfunded—and [has] been for years.”15 Who funds Lean? How will it be protected against technical obsolescence?16 What guarantees the long-term digital archiving of its library of proofs?

Not only gainful employment will inevitably be lost in the mechanization of mathematics. Who is talking about that?

The technological workplace that invites us to think about ourselves

The conception of authorship on which our current anti-plagiarism conventions were built is a conception that does not reflect our current technological reality, and that does not preserve or cherish any conception of the humanities capable of carrying them, alive, into our uncertain future. (Justin E. H. Smith)

Luddism didn’t start with the Luddites. In 1741 King Louis XV charged Jacques de Vaucanson, inventor of the defecating mechanical duck, with improvement of French silk manufacturing. “Vaucanson sought to produce a robot that would eliminate the human problem” of uneven quality. “Vaucanson’s looms in Lyon,” which incorporated the knowledge he had acquired in designing automata to hold threads in tension,

were “meant to show man that he was dispensable.” Lyonnais weavers assaulted Vaucanson in the streets17 whenever in the 1740s and 1750s he dared appear …Thus began the classic story of displacement of craftsmen by the machine. (Richard Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 87)

Colleagues transfixed by the prospect of “exciting progress” may forget that when technology moves fast it doesn’t have to break people as well as things. In his concerts as well as in his interviews Frisell comes across as a craftsperson, like the Lyonnais silk weavers, whose primary motivation is:

an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake. (Richard Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 9)

In contrast to Vaucanson, Diderot and D’Alembert, in their Encyclopédie, also “celebrated those who are committed to doing work well for its own sake,” according to Sennett. Jean Dieudonné, speaking for Bourbaki, saw mathematics like that as well:

…one always has the impression that one is working like a craftsman, by accumulating a series of stratagems.18

The prophets of automation may not “cherish any conception of” human mathematics; but the crafts perspective is not necessarily incompatible with mechanization. Sennett writes that “a robotic machine”

is ourselves enlarged: it is stronger, works faster, and never tires. Still, we make sense of its functions by referring to our own human measure. (Sennett, p. 85)

It is, according to Sennett, a “mirror-tool … an implement that invites us to think about ourselves.” Mechanized mathematics can also be like that19; but only if colleagues abandon the belief that it will all come out well in the end thanks to the operation of “the market.” Most of my colleagues have already distanced themselves from this belief as it concerns matters such as protection of the environment or the election of those who govern us, or the protection of the creative efforts of craftspeople. Where, then, is the organized resistance among mathematicians to the Big Tech vision of “turning human behavior into a raw material”? Is this vision relevant to mechanization of mathematics?

In his chapter on “Planning for Mass Unemployment”, already cited, in the collection of essays entitled Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, Aaron James unexpectedly alludes to the paradox to which mathematicians, like Sennett’s craftspeople, are subject, insofar as their income depends on their employment.

It is an undesirable feature of a society that people are forced to find a way of monetizing the activities they love, simply to have enough time to pursue them vigorously.

The simplest solution to this paradox would be to dismiss consideration of love or anything that one might “cherish” as an organizing principle in the design of the mechanized future. In the absence of any serious consideration of the material circumstances and the motivations that underpin contemporary mathematics, this would also appear to be the default solution.

When I started writing this installment…

Although it can also be that, of course.

A future newsletter will contrast the vision of “computers tak[ing] over [mathematics] completely” with the vision of mathematics as (what I have called) “a way of being human,” as developed in the excellent new book Mathematica by David Bessis.

Authors, not generators!

Paul Elie, “Nobody Plays Guitar Like Bill Frisell,” The New Yorker, May 16, 2022.

From Aaron James, “Planning for Mass Unemployment: Precautionary Basic Income,” DOI:10.1093/oso/9780190905033.003.0007.

Quoted in George Seligman, Most Notorious Victory: Man in an Age of Automation, p. 227.

Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil.

Marc Levinson, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, pp. 168-69.

Aaron James, op cit.

Gavin Mueller, Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Are Right about Why You Hate Your Job, Verso (2021).

The authors add that “The negative relationship between wage changes and task displacement is unaffected when we control for changes in market power, deunionization, and other forms of capital deepening and technology unrelated to automation.”

According to Tavlin, citing the report’s figures, "An average two-hour movie shot and archived on film cost only $486 per year to store. Its 4K equivalent? A staggering $208,569 per year.”

Not to mention the no less inevitable evolution of the priorities of the branches of mathematics it pretends to memorialize.

Possibly including the street now known as rue Vaucanson, on which I dared appear in Lyon the last week of June.

“The work of Nicolas Bourbaki,” The American Mathematical Monthly Vol. 77, No. 2 (Feb., 1970), pp. 134-145.

My belief that “thinking about ourselves” as human beings is a positive value puts me at odds with posthumanists, of course.