“Bubbles are good”

“Is it just a Ponzi scheme?” asked Gillian Tett in her October 17 Financial Times article under the title “AI has a cargo cult problem.” Headlines like these, also from the Financial Times

The AI bubble is a bigger global economic threat than US tariffs

and

Bubble-talk is breaking out everywhere

are appearing literally every day, in the financial press as well as in generalist news media. The same day the Financial Times published yet another such article:

“Of course there’s a bubble,” said Hemant Taneja, chief executive of venture capital firm General Catalyst, which raised an $8bn fund last year and has backed Anthropic and Mistral. “Bubbles are good. Bubbles align capital and talent in a new trend, and that creates some carnage but it also creates enduring, new businesses that change the world.”

Did tulipmania create enduring new businesses? During the five days I recently spent at the Lorentz Center in Leiden I saw lots of canals, and exactly one windmill, but not a single tulip, nor even an allusion to tulips: not in town, nor during the workshop on Mechanization and Mathematical Research that brought several dozen mathematicians, computer scientists, historians, philosophers, and at least one anthropologist, to rainy Leiden in mid-September.

Of course it’s not only the Financial Times that’s sounding the alarm. It’s also Fortune, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Les Echos, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung… So many articles are predicting a bubble that it has generated a secondary literature of meta-bubble talk, as in today’s Financial Times article, entitled “The political economy of Trump’s luck,” by the always lucid Edward Luce.1 Since it’s behind a paywall, I’ll share the paragraph most relevant for my purpose:

Naturally, liberals are focused on ensuring that Trump takes the blame for the AI crash that has not yet happened. If there is a big correction, as there eventually must be, Trump will be deservedly blamed. But as my colleague Robert Armstrong recently observed of financial journalists, Trump’s opponents suffer from negative bias and thus often miss upturns. Americans see their economy through a partisan lens, according to years of polling. If the economy deserves to be bad, then it surely must be. And what could be more self-harming than so many trade wars of choice?

The message of this paragraph, and of Luce’s title, is that the recent bubble-prediction bubble may be a symptom of wishful thinking, on the part not only of “liberals” but of anyone who is concerned that liberal democracy, such as it is, along with the rule of law, can’t possibly survive another 3 years and 3 months of this administration, and that a bursting bubble is the only force that can halt the destruction.

I must confess that I share this tendency to what you might call anticipatory Schadenfreude, and for a second reason as well, which is that an end to the limitless expansion of investment in data centers and math-adjacent startups would force the industry to reveal the true depth of its interest in mathematical research. Unfortunately, I suspect (as I’ve already predicted) an authentic AI crash would mainly serve to intensify the industry’s dependence on military and surveillance applications.

Declaration or manifesto? Does it matter?

In his recent London Review of Books article, James Meek gave a helpful and concise list of reasons to be upset about AI models:

…their massive energy use, their ability in malign human hands to create convincing fake versions of people and events, their exploitation without compensation of human creative work, their baffling promise to investors that they will make money by taking the jobs of the very people who are expected to subscribe to them, their acquired biases, their difficulty in telling the difference between finding things out and making things up, their de-intellectualising of learning by doing students’ assignments for them, and their emerging tendency to reinforce whatever delusions or anxieties their mentally fragile human users already carry…

Meek had LLMs in mind, but most of this adapts nicely to any of the hypothetical AI projects that everyone present at the Leiden workshop expects to see being imposed on mathematics, or perhaps welcomed, sooner or later. Concerns like these emerged at the workshop, more frequently in the breakout room discussions that ended each of the middle three days of the program, rather than in the extended presentations that were the main items on the schedule. But the possibility that all this hand-wringing might be moot, if the AI bubble bursts, seems not to have been mentioned at all.

For these and many other reasons, it’s timely that participants in the Leiden meeting agreed to formulate a kind of declaration of principles to govern future applications of AI to mathematics, and the relations of mathematics to the tech industry. The draft of such a declaration that I included during my own presentation stressed the importance of preserving the autonomy of the profession. It was intended to serve to stimulate a wide-ranging discussion, and it was already amended during the workshop in response to comments. Afterwards I regretted not mentioning the danger that, by yoking itself too closely to the industry, mathematics would become subject to the hazards of the business cycle.

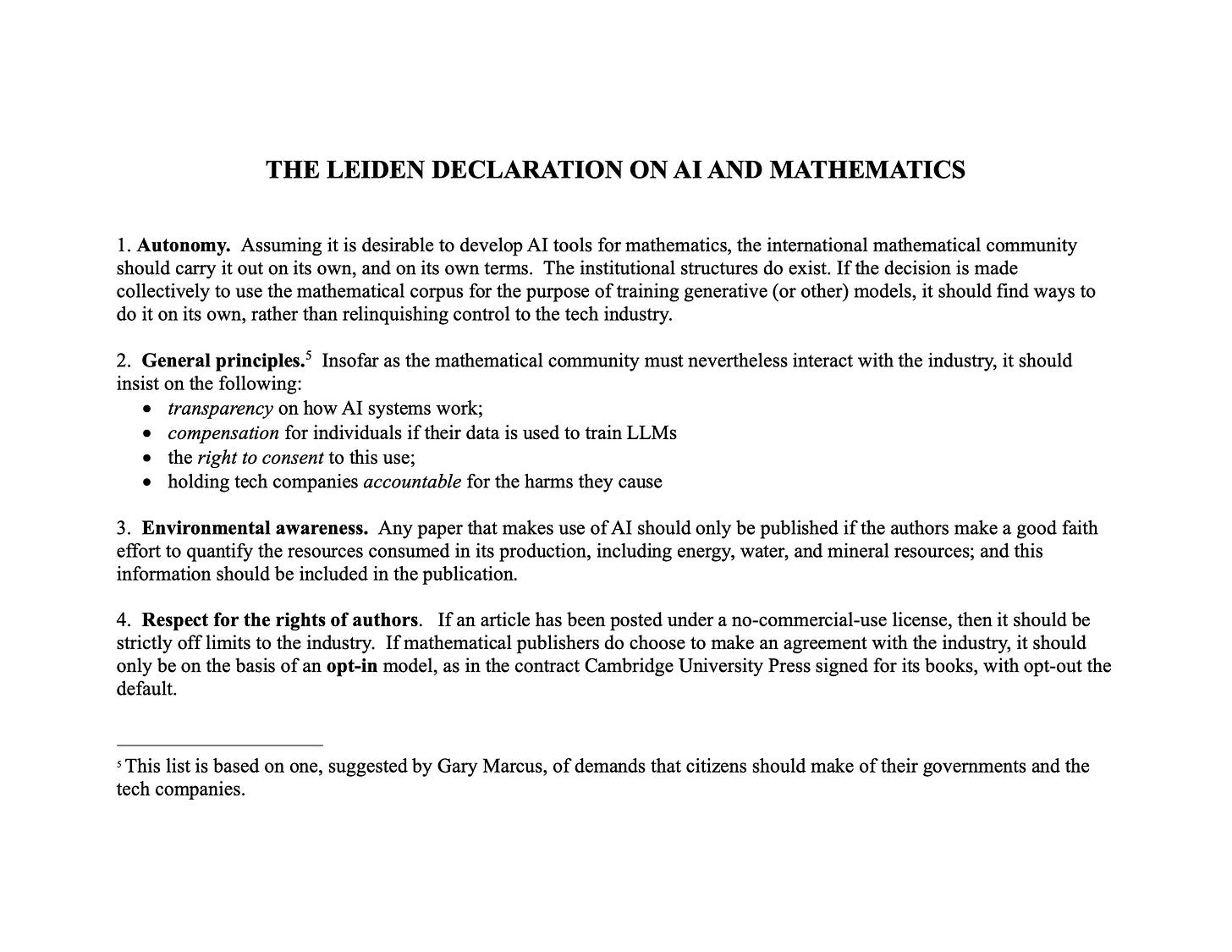

Here is the slide containing my proposal for a Leiden declaration:

A group has been convened, and is meeting regularly, to draft an official “Leiden declaration,” using this text and suggestions by other participants as a starting point. Since the group of participants in the Lorentz Center meeting does not and cannot pretend to represent the entire community of mathematicians, our hope is that the document that is produced at the end of this process will be sufficiently convincing to be adopted by a number of professional associations. No date has been proposed for completion of the declaration, but wouldn’t it be appropriate if it were ready by the next time the tulips bloom?

Turbulence (a preview)

My original intention was to continue this post with a discussion of something I was told in Leiden. I had been told earlier this summer that experts were expecting that the Navier-Stokes problem would be the next of the million-dollar Clay Millenium Prize problems to be solved; but it was only in Leiden that I learned that already in June it had been announced in the Spanish daily El Pais that, to quote the subtitle of the article,

Apparently the secret was widely known but had not previously been shared with me. I was planning to share my own thoughts about

The role of AI in the attempt to solve the Navier-Stokes problem; and

How DeepMind will frame the story if and when the problem is solved.

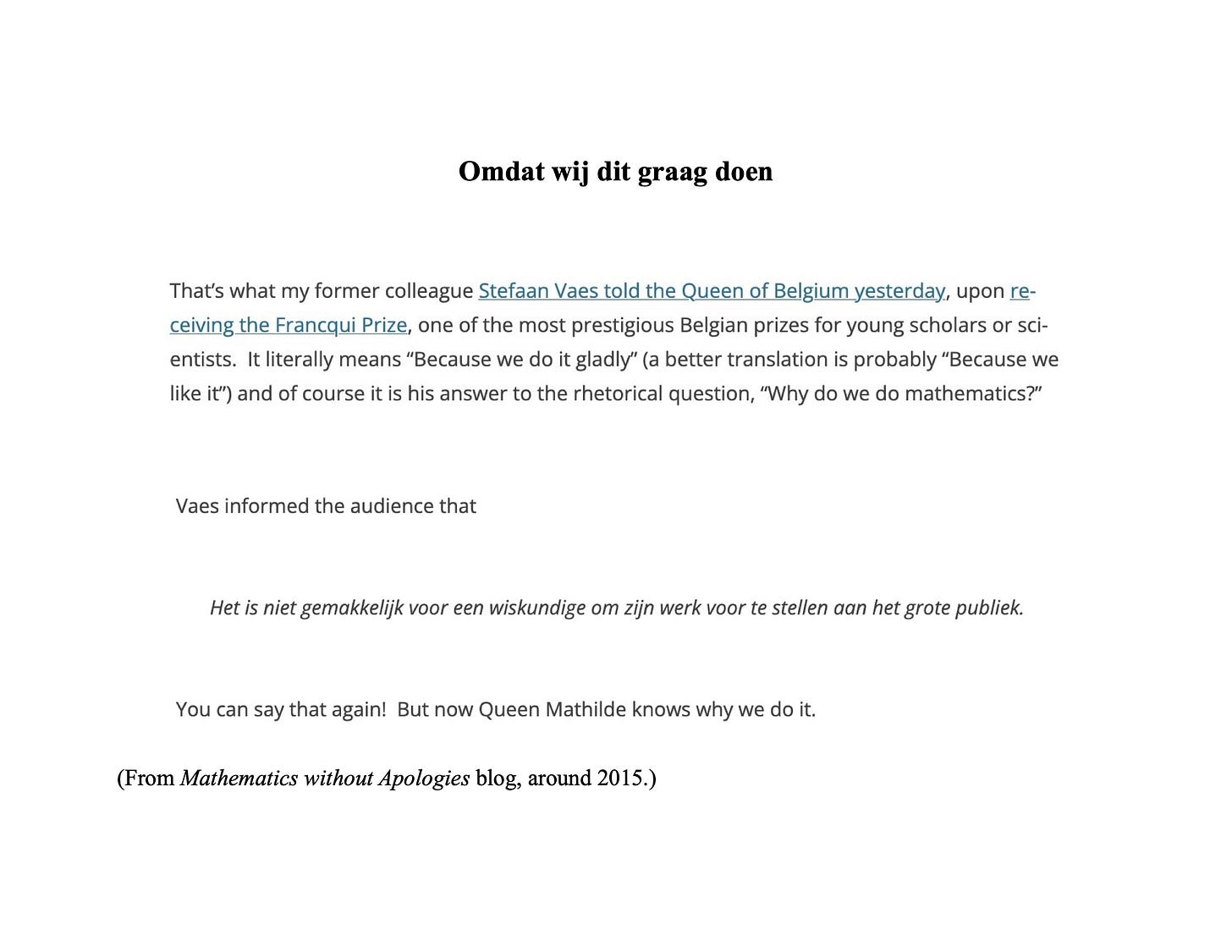

But time is running out, so this will have to wait until my next post. In the meantime, here are a few more slides from my Leiden presentation, which was entitled

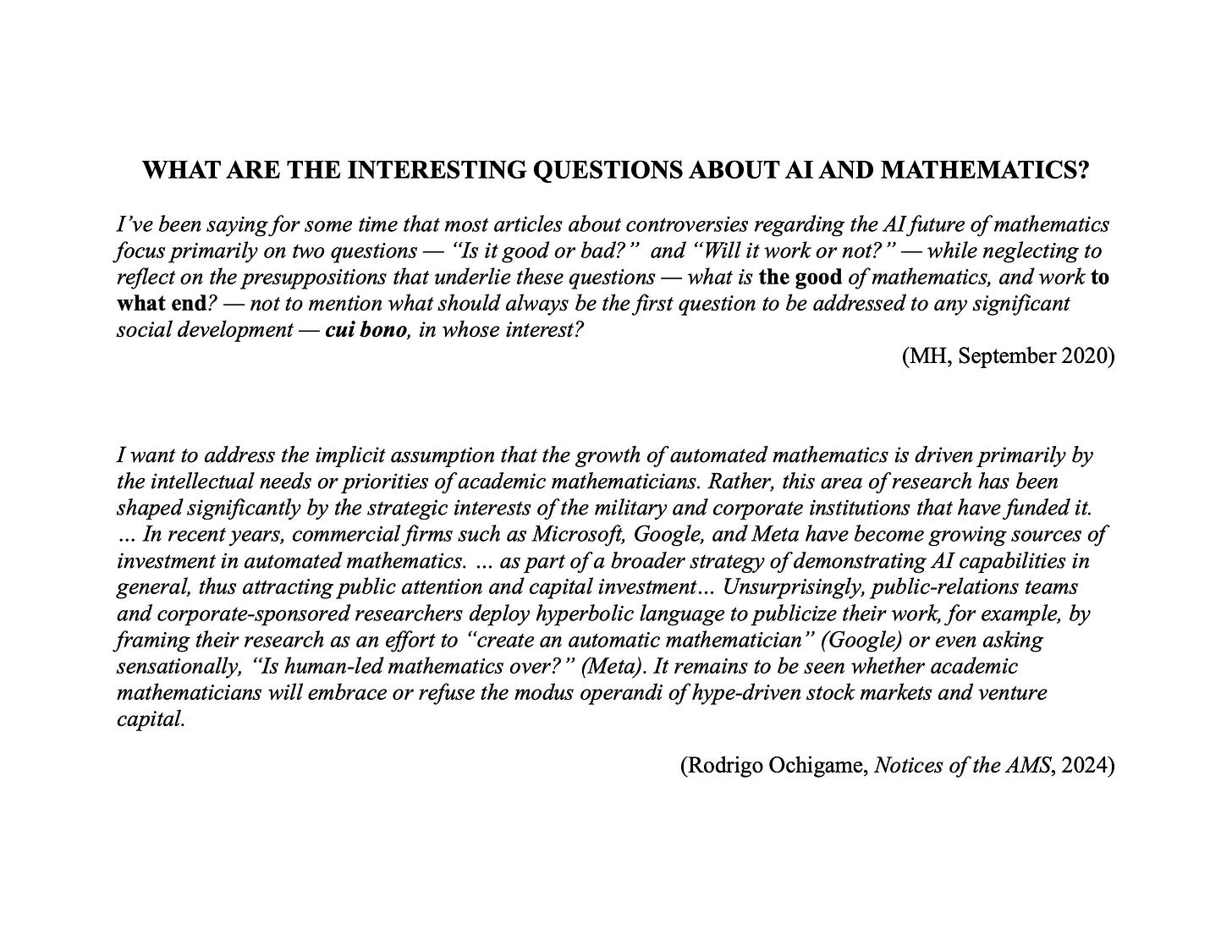

Why do we ask ‘why do we do mathematics?’

[Added several days later] The Financial Times has yet another meta-bubble article (behind a paywall), called “Safety strategies for a bubble market” by Katie Martin, which even cites “investors who think the only bubble here is a bubble in people talking about bubbles.” Martin is not convinced by all the bubble talk but her conclusion is not especially reassuring:

if the AI trade is a bubble (still an if) and if it pops soon (also still an if), then at least in the short term, nothing would be spared. “At an index level, everything would fall,” says Ed Smith, co-chief investment officer at Rathbones Investment Management in London. Smith is not in Team Bubble here but, as he notes, the dominance of index-tracking passive funds these days means that to a large extent, everything rises and falls together.

This math-washing of LLMs is so sinister, it adds legitimacy to big companies products and it impoverishes the public’s view of who a mathematician is and what they do. I work in journalism and see so many press releases about ‘AI scientists’ along the same lines and it’s disconcerting how quickly that language caught on, university press offices are using it too.

Dutch tulips are big business, you see lots of illuminated glasshouses when you fly over NL at night