The conversation on AI mathematics is expanding

Preparing for a workshop in Leiden

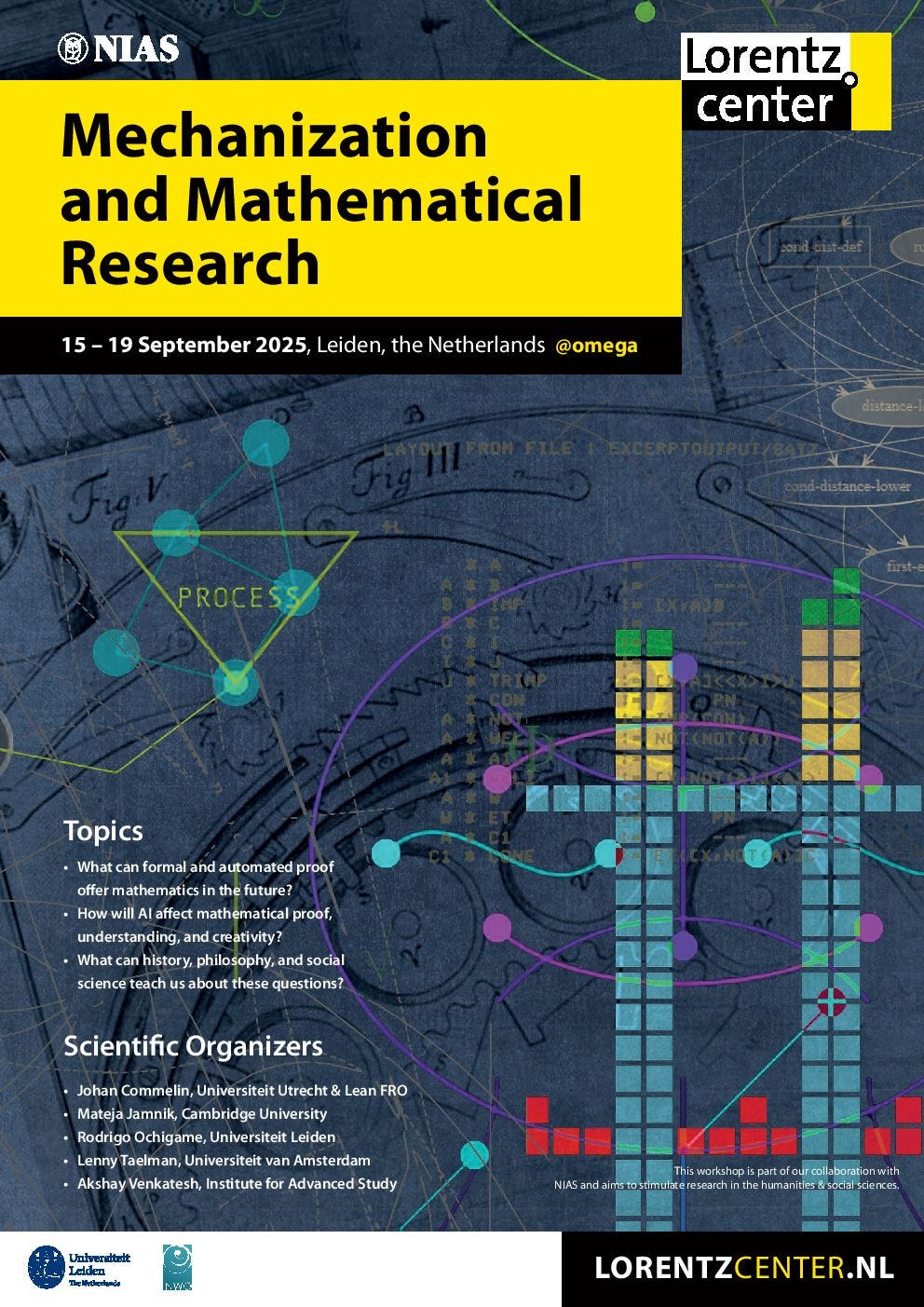

Over the last few weeks I have been busy preparing my presentation for the workshop that will take later this month in Leiden. The preliminary program has just been made public. When you read it these titles are likely to stick out:

Is Mathematics Obsolete?

Will mathematics exist in 2035?

These are not only odd questions to ask in Leiden, home of Spinoza, who notably introduced the notion of conatus, the tendency of anything to strive to persevere in its being,1 or as Spinoza put it:

PROPOSITIO VI. Unaquaeque res, quantum in se est, in suo esse perseverare conatur,

translated here as

Everything, in so far as it is in itself, endeavours to persist in its own being.2

In Leiden, of all places, it should be understood that mathematics is “in itself” and thus shares this tendency, perhaps more than most things. So you might think the workshop’s first job, in response to such titles, would be to figure out just what is the esse of mathematics. In the present media environment, however, and whether or not the speakers plan to offer reassuring answers to their questions, framing them in this language is a dangerous concession to what I called progressive defeatism in my previous post. If the workshop attracts any press coverage at all you can count on3 seeing headlines like

Mathematicians ask: will they soon be obsolete?

Does anyone think this kind of attention would be a good thing? Is anyone in any doubt as to how those individuals and political structures currently in a position to make decisions about the future of mathematics would interpret such a headline?

I was asked to speak on the topic “Why we do mathematics.” As usual I find it more fruitful to question such a question, as I just did with the two bullet-point questions above, rather than to try to answer it. My book Mathematics without Apologies was to a large extent an account of unsuccessful attempts, mine included, to find a definitive answer to just that question, primarily with reference to the kind of pure mathematics that is my specialty. To a much lesser extent, the book was devoted to an effort to highlight some very partial answers, based on what mathematicians actually say when confronted with that question. Even earlier, I questioned the same question in the title of my chapter in The Princeton Companion to Mathematics.

For this reason I have to say I feel disappointed when I see titles like those quoted above. After writing texts over more than 20 years about what you might call the ethos, or the relaxed field, or the tradition-based practice, or the structure of feeling, or the conatus of the community of mathematicians, I would like to think that my colleagues would cease to entertain the vision of mathematics as a spigot that can be turned on or off. The minimal ambition of this Substack newsletter is to encourage colleagues to treat the obsolescence of mathematics not as the subject of a legitimate yes or no question but rather as a theme, whose emergence, in its most recent manifestation, is associated with the material interests of identifiable social agents, most of them demonstrably disreputable. Seeing such titles I have to conclude that this newsletter has failed to realize even this minimal ambition.

(Nevertheless, Substack always reminds me to include a “Subscribe now” button somewhere, and this place is as good as any.)

My own chosen title, “Why do we ask ‘why do we do mathematics?’” literally questions the question. But I’ll still be devoting most of my presentation to questions raised by mechanization, because they provide the context in which I was asked to speak. I plan to share most of my presentation after it takes place. For now, here is the list of topics I’ve chosen to structure my talk:

If when we speak of AI we mean corporate AI, its primary goal will be to seek profit, and AI-based mathematics will have to adapt.

The global economy may well be reorganized in a way that is indifferent to "why we do mathematics" and to the principles on which the research university has been based for (at most) two centuries.

In the meantime, look to other academic disciplines — especially the humanities — whose assigned role in the educational division of labor is to teach us to think about why we do anything. (Find 10 convincing reasons humans won't be obsolete by 2035. It's not so easy!)

If we don't agree on what mathematics is, how can we speculate on its obsolescence? Don't forget that philosophy of mathematics can hardly be reduced to instrumental reason.

And don't ignore the dozens of books and films, hundreds of op-eds, as well as pop culture, that express ambiguity, if not outright hostility, to the Silicon Valley mentality.4

How to explain the peculiar susceptibility of mathematics, among academic disciplines, to (the corporate variant of) what Evgeny Morozov calls solutionism?

Time permitting, I'll end with a brief account of my own limited experiment with AI in mathematics.

I will also make a point to insist on factors that mathematicians generally neglect when talking about AI:

Democracy

Concentration of wealth

Natural resources

Energy and water consumption (even Google is paying lip service to this)

Copyright violation

Since my presentation comes close to the end of the week, I will have had the chance to mark down whether or not speakers have mentioned any of these issues.

Look at the list of speakers and you’ll see that the organizers have created the conditions for a very broad dialogue. In addition to mathematicians and computer scientists, participants include historians, philosophers, cognitive scientists, and at least one anthropologist, as well as people working in the industry. This is why I chose to emphasize that “the conversation is expanding” in the title of this week’s installment. Such a conversation can only be a good thing. However, it’s only fair to those in the last-named group to state here that, whatever they think they are doing, and whatever their intentions, I don’t trust them. The reasons for this are easy to find in the books quoted in this post.

About which I wrote, in my article for the AMS Bulletin special issues on the topic “Will machines change mathematics,”

You might think that a profession's very first steps, upon pledging to live deliberately, would be to clarify the nature of the "being" in which it "strives" — its Spinozian conatus — to persevere; and, having done that, to reflect on the material conditions without which its striving is futile. For the profession of mathematics, the conatus is largely concerned with the values highlighted in Venkatesh's essay. It is exceedingly rare, however, for mathematicians to undertake such a reflection.

These special issues grew out of this meeting at the Fields Institute in October 2022. The Lorentz Center workshop is a follow-up to that meeting, with a broader participation.

Spinoza calls this a Proposition, so its statement in Ethics 3 is naturally followed by a proof. If you read the proof you will notice that it is based on Propositions from earlier sections about God. But what Spinoza defines to be “God” is really a placeholder. I strongly suspect that the proof of Proposition 6, when accompanied by Spinoza’s definitions, would survive formalization and would compile successfully in Lean.

If you don’t believe me, see the magazine cover reproduced at the bottom of this early post, and the title of this New York Times article. In both cases the title was chosen by the editors and not by the journalists.

I see hundreds of such items every month. Just last week I saw what may be the best article I've read about "Why we do mathematics" that doesn't mention mathematics: Joshua Rothman, "A.I. Is Coming for Culture," The New Yorker, August 25, 2025.

[T]he story of A.I. is not only practical; it’s also moral and spiritual… it is already forcing us to think about what we value, about what really makes us care.

Terrific post Michael. Much looking forward to see/hear your presentation when you post it! As to 10 reasons why humans won't be obsolete by 2035: in one word "Children". AI's will never be able to bring up children. No matter how hard the Dudes try to force their stuff on us, children will always need humans to help them to become the new generation of humans. Of course the whole project of humanity could be ditched. And with the increasing likelihood of nuclear war it may well be. I would argue that conatus applies above all to humans, who strive to continue to exist For Ourselves. I loathe the instrumentalization of Us proposed by the tech overlords. As Goethe so well said: "Every creature is its own reason for being."