Terence Tao on Machine-Assisted Proofs

Thoughts on an article published in the January 2025 issue of the AMS Notices

The January 2025 issue of the Notices of the American Mathematical Society opens with an article entitled Machine-Assisted Proof by UCLA Professor Terence Tao. I have to assume it’s not a coincidence that this is appearing just in time for next month’s Joint Mathematics Meeting in Seattle which, as I’ve mentioned previously, has chosen AI as its “official theme.” If the AMS, as the world’s leading professional organization of mathematicians, and the main organizer of the Seattle meeting, feels it has to pay special attention to AI — not only with this “official theme” and Tao’s article but also with the two issues of the AMS Bulletin to which I contributed, and the consultation mentioned here a year ago1 — it may only be because all of us are constantly being prodded to pay special attention to AI. Frankly, I would have much preferred to see ChatGPT named Time’s “Something of the Year,”2 rather than Donald Trump, but everyone’s favorite LLM came out a year too soon, and Time preferred to give that year’s honor to Taylor Swift.

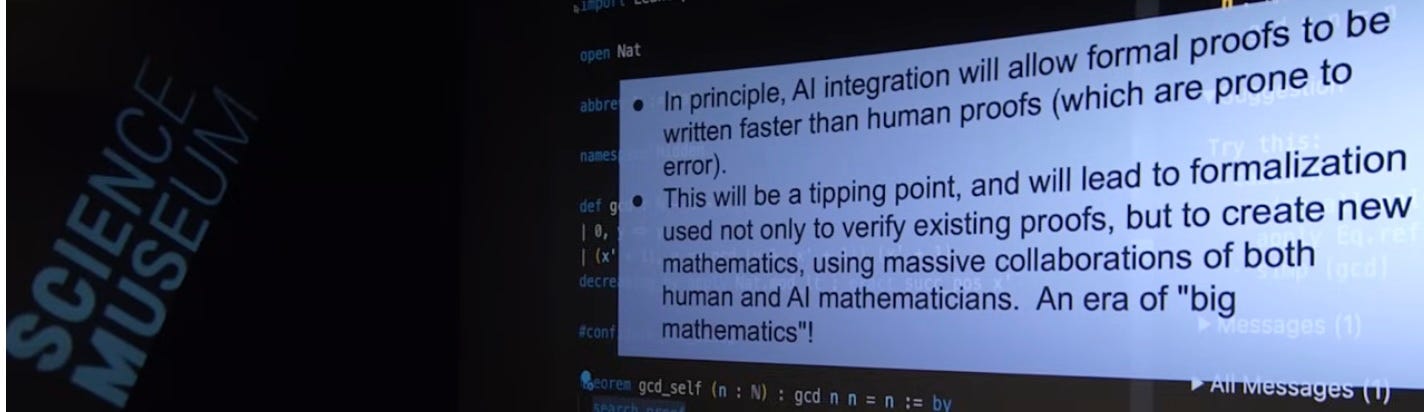

Tao’s article, however, is premised on the notion that mathematicians should be paying special mathematical attention to AI, now and in the near future. I'm tempted to add — “whether we like it or not” — but Tao argues that we are going to like it. In what follows I will not deny that he makes a pretty good case,3 and a better one in his lecture to a packed auditorium at the Science Museum in London last July, which you can watch at the YouTube link pictured above. My aim here, however, as in my presentation at the Special Session on Mathematics, AI, and the Social Context of Our Work at the JMM in Seattle, is rather to point out what Tao’s article, and for the most part his London lecture, did not mention about the potential implications of AI for mathematics.

The Tao of Mathematics

But I should first say a few words about Terence Tao — or Terry, as everyone calls him — for the benefit of the majority of readers, who are not mathematicians. It would be both tautological and not completely unambiguous to call him “The Tao of Mathematics,” although it would not be the first time; but John Baez had already4 given that name to something else:

Terry Tao has been more frequently called the “Mozart of mathematics,”5 both for his early emergence as a prodigy and because of his virtuosity and versatility — as a UCLA colleague wrote, “mathematics just flows out of him.” That was written when Tao received the Fields Medal, still the most prestigious prize in mathematics. Not the most lucrative prize — but Tao won that one, too, and most of the other available prizes as well.

But this comparison still doesn’t do justice to Tao’s influence on contemporary mathematics. Had Mozart actually been the Tao of Music, he would have had to be not merely a composer and conductor and have played most of the instruments; he would also have been organizer of massive collaborative efforts, and universal music critic6, and educator, not to mention human rights ambassador with his participation in 2023 in a conference organised simultaneously in Warsaw and Kyiv by the International Centre for Mathematics in Ukraine. And we would have seen Mozart on the Colbert Report.

Curiously, this reference in the last footnote was found in the middle of an exchange on the n-category café in which the human Tao is representing the “problem-solving culture” of mathematics opposed to the culture of Baez’s “tao of mathematics.” Tao is placing his work, in other words, at the opposite end of a continuum from the “typical Grothendieck proof,” a style of proof where things constantly “seem[] to happen”; and we actually would be willing to say that “things happen” in a Terry Tao proof except that we don’t know how to assign grammatical tense to the steps in a mathematical argument — or do we? So here’s a question to keep in the back of our minds as we suspend our disbelief and explore Tao’s foray into the future of mathematics in what some insist on calling the “Age of AI”:

Will AI math’s Tao be the Terry or the Grothendieck version, or something in between, or neither?

As a stimulus to meditating on this question, I don’t advise reading what mathematicians write on the subject, which by now is so predictable. Instead, I can’t recommend strongly enough last year’s essay “13 Ways of Looking at AI, Art & Music” by the Irish composer and performer Jennifer Walshe. Here are two mind-opening quotations from that essay:

How, and why, was this experience facilitated? Who funds it? Who benefits? What relationships am I expected to enter into? What agency do I have? How am I activated by the work? How do I activate it? Am I locked into the role the work allocates to me? Or is it possible for me to intervene? To protest? To refuse?

This is the fate of all AI-generated material. Even when the networks develop to the point where they produce only pristine images and songs, they will still be gunk, because they will still behave like gunk.

Walshe asserts that “AI is not a singular phenomenon” and devotes considerable creative energy to conjuring images of AI as the springboard for utopian fantasies, as matrix of philosophical reflection, as the focus of a massive and potentially sinister gamble on the part of investors, and much else. You can find support for either variant of the “Tao of mathematics” among the 13 sections of Walshe’s text, inspired (as mathematicians should be more often) by the Wallace Stevens poem. What her essay does not allow is to squeeze AI into the imaginative strictures of a corporate mindset.

Importing management practices… and values?

Because, while Tao’s essay can hardly be accused of subordination to a corporate mindset, its failure at any point to acknowledge that development of the technology called AI is largely being driven by the agenda of the tech industry and the venture capitalists and government contracts that sustain its position as the most lucrative industry of all time — whose principal goals are and always have been to guarantee an enormous return on investment and to maintain a favorable posture in anticipation of a future automated arms race — abstracts from the all-too-human decision-making process that takes place in the boardrooms and laboratories of Silicon Valley and its satellites, envisioning technological development as autonomous and inevitable.7

Thus, in the middle of a speculation on how AI might replace “pages of calculation” by an automated procedure, Tao writes

I see no reason why this sort of automation will not be achievable as technology advances (my emphasis)

as if the technology were a self-driving tank or bulldozer. If AI is really going to transform the practice of mathematics, it is urgent that mathematicians stop talking this way if we are to have any hope of preserving the values of the profession.

It’s telling that, in his section on how AI can facilitate large-scale collaboration — as discussed in more detail in the section below on “Big Math” — Tao uses the expression project manager for the role of coordinating the collaboration, rather than any of the alternative metaphors the come to mind: orchestra conductor, impresario, stage manager, artistic director, choreographer, director of the Impossible Missions Force, or simply team leader.

I would have used team leader to translate my official role in the automorphic forms group in Paris, but for reasons connected with the structure of the French public administration, which is quite different from but no less hierarchical than corporate management, I was called chef d’équipe, literally team boss, or baas as in Afrikaans.

Here, anyway, is what Tao writes:

In time, the large collaborations that are already established practice in other sciences, or in software engineering projects, may also become commonplace in research mathematics; some contributors may play the role of “project managers,” focusing for instance on establishing precise “blueprints” that break the project down into smaller pieces, while others could specialize to individual components of the project, without necessarily having all the expertise needed to understand the project as a whole.

I asked perplexity.ai how the expression “project manager” is most frequently used, and this was its answer:

the term "project manager" is most frequently used in industries such as corporate business, construction, IT, and healthcare, with a significant presence in regions like the United States and the United Kingdom.

Tao made the corporate connection explicit in his talk at London’s Science Museum, referring specifically to the analogy with software development, when he introduced his vision of the “project manager”: not necessarily a technical expert but a good “people person.” It’s not as if Tao is unaware that the industry’s centrality to the development of the new technologies is problematic in the long term. In his London talk he acknowledges that

private industry has orders of magnitude more resources… In developing the biggest models… there’s no way academics can compete.

Disappointingly, Tao doesn’t speculate on how society might be structured differently, so that academics could compete; however, later in the same talk he hints that the mathematics community, at least, could recover control of the technology for its own purposes:

The current AI models are really energy-intensive and compute-intensive… we need more research to find more lightweight models that can fit on a computer that can be put in a lab.…

adding — since someone has to pay for this research —

that’s actually one area where I think public funding can be quite useful.

Remember this thought when you reach the end of this post!

Big Math

Google’s top hit for “Big Science” is not the Stanford University Press book edited by Peter Galison and Bruce Hevly and published in 1992, but rather the Laurie Anderson album of the same name that came out 11 years earlier. “[A]s a first approximation,” Andrew Pickering wrote in his review of the book,

one can say that a science becomes big science when its funding levels become non-negligible on the scale of advanced national economics.

According to Pickering, the first manifestation of science on such a scale, apart from the Manhattan Project, was the “development of microwave radar techniques,” which, as told by Galison, Hevly, and Rebecca Lowen, provided Stanford physicists the opportunity “to integrate themselves into the circuits of industry via an emphasis on the construction and development of useful devices.”

Tao, a pioneer in the use of technology for the purpose of large-scale collaborations, repeated the expression “big math” several times in London, once with the exclamation mark shown above; though he never went so far as to predict that its funding levels would reach Pickering’s threshold of non-negligibility on the national scale. Tao regretted in his London lecture (at 23:17) that

we don’t have the big math projects that we have in the other sciences.

He blames this on a “huge bottleneck” inherent in traditional practice that only grows with the size of the collaboration —

you have to all trust everyone else’s mathematics

— but argues that “you don’t need the same level of trust” in a large-scale formalization project, since the system checks correctness. “The great promise of these formalization projects,” according to Tao, is how they “decoupl[e] the high level conceptual skill from the low level technical skill.”

Reminded by the moderator that professional incentives discourage such decoupling, Tao argued that “the academic publishing system is already coming under strain” and anticipated that “funding agencies will have to figure out new ways” to measure a contribution to a massive collaboration.

Tao sees big math as a way for people without advanced mathematical training to participate in massive collaboration; he even sees a role for the broader public in mathematical research, analogous to “citizen science” in fields like biology or astronomy. Unfortunately, the history of automation suggests a different model, and I’ll repeat a quotation I published here three years ago:

In a passage that Babbage was to repeat like a refrain, [Gaspard de] Prony marveled that the stupidest laborers made the fewest errors in their endless rows of additions and subtractions: “I noted that the sheets with the fewest errors came particularly from those who had the most limited intelligence, [who had] an automatic existence, so to speak.”8

Tech bros react to Tao's article

Reaction on Twitter has been particularly unkind. Someone named λy called Tao’s January 2025 article

well written but - as of today - … out of date before it even turned Jan

Aran Komatsuzaki claimed that Tao’s reputation for “perspicacity” is undeserved, revealing in the process why it’s futile to argue with tech bros:

The inevitable Christian Szegedy chose to damn Tao with faint praise:

A few months ago, I had a long chat with Terry Tao. While he is one of the knowledgeable and forward-looking mathematician [sic], I still had the impression that he was out of touch withe the reality that was coming up quickly.

“Forward-looking,” in Szegedy’s mind, means ignoring one’s surroundings, like a horse wearing blinders, so his characterization of Tao is certainly inaccurate. His exceedingly optimistic timeline for AI mathematics9 may be dismissed as the ravings of a megalomaniac. But this is to forget that we’re dealing with the reflected megalomania of the man who would be everyone’s baas, and who has been Szegedy’s baas ever since he was bumped up the food chain from Google to xAI.

Neglected externalities

If you have been skimming the text up to now you may have missed how Tao mentioned that current AI is “energy-intensive.” This was the only allusion to the technology’s environmental cost in his London talk; in his Notices article such considerations are totally absent. If you want to learn how AI and computing technology more generally are accelerating the devastation of the planet, nothing that mathematicians have written will be of much help. Instead, you’ll have to look… practically anywhere else, but your first stop should be Kate Crawford’s irreplaceable Atlas of AI, which I will be reviewing early next year. This quotation from Crawford’s book neatly summarizes her perspective:

Artificial intelligence is not an objective, universal, or neutral computational technique that makes determinations without human direction. Its systems are embedded in social, political, cultural, and economic worlds, shaped by humans, institutions, and imperatives that determine what they do and how they do it. They are designed to discriminate, to amplify hierarchies, and to encode narrow classifications. When applied in social contexts such as policing, the court system, health care, and education, they can reproduce, optimize, and amplify existing structural inequalities. This is no accident: AI systems are built to see and intervene in the world in ways that primarily benefit the states, institutions, and corporations that they serve. In this sense, AI systems are expressions of power that emerge from wider economic and political forces, created to increase profits and centralize control for those who wield them. But this is not how the story of artificial intelligence is typically told.10

Is it too much to ask mathematicians to remember this when speculating about the discipline’s AI’s future? Or are the practical implications of such thinking too nebulous? If I were editing the AMS Notices, in any case, or overseeing NSF grant applications, I would require proposals to mechanize mathematics to include energy ratings, like new appliances or buildings in New York City. Also carbon and water ratings, to mention a few of the externalities Crawford highlights (as do so many other authors). How much energy and water would be needed for the proposed project? What would the CO2 emissions be?11

[T]hat’s actually one area [as Tao might have said] where I think public funding can be quite useful.

Much more useful, in any case, than requiring research articles to be accompanied by formalizations.

Whatever happened with that consultation, by the way?

In 1982 The Computer was named “Machine of the Year.”

He refers, for example, to a 2019 paper by Wang, Lai, Gómez-Serrano, and Buckmaster,

who used a Physics Informed Neural Network (PINN) trained to generate functions that minimized a suitable loss function measuring the extent to which the desired PDE and boundary conditions are being approximately obeyed. As these functions are generated through a neural network rather than a discretized version of the equation, they can be faster to generate, and potentially less susceptible to numerical instabilities.

I have no reason to doubt Tao’s conclusion here that “the machine learning paradigm shows great potential.” On the other hand, I found it a little disconcerting when he writes about

explaining a result in natural language to an AI, who would try to formalize each step of the result and query the author whenever clarification is required. (my emphasis)

The first record I’ve found is here in 2007, after Terry Tao had already received his Fields Medal, but it is understood there that Baez had been using the expression for some time.

However, Jean-Pierre Serre has also been called le “Mozart” des maths. And Serre was even younger than Tao when he won his Fields Medal.

This and the next are an allusion to Tao’s blog, in which he posts more in an average month than a typical mathematician writes in a year.

This is a long sentence! I asked ChatGPT to make it more readable, and it obliged by breaking it into three sentences that meant roughly the same thing; but I preferred to keep my own version.

Lorraine Daston, “Calculation and the Division of Labor 1750-1950.” In the 1820s de Prony pioneered industrial-scale calculation by creating a pyramid of logarithm calculators, with the mass of workers at the bottom. Matteo Pasquinelli’s The Eye of the Master, which is overdue for a review here, cites de Prony and Babbage, and traces the history of automation as a largely successful effort to transfer control of production from those who operate machines to their owners.

Progress is faster than my past expectation. My target date used to be ~2029 back then. Now it is 2026 for a superhuman AI mathematician. While a stretch, even 2025 is possible.

Here he seems to be predicting that the Langlands program would be solved in 2024. But perhaps this prediction was intended as humor.

Crawford, Atlas of AI, p. 211.

I have absolutely no idea why YouTube chose to insert an indelible link about climate change when I copied the link to Tao’s talk. Do you see the same thing?